Beta Decay: Equations, Feynman Diagrams & Measurement

Beta decay, a term coined by Ernest Rutherford in 1899, describes a class of radioactive decay processes that involve the emission of either energetic electrons or energetic positrons. These reactions are known as beta minus decay (β-) and beta plus decay (β+) respectively, and the emitted electron or positron is often referred to as a beta particle.

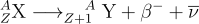

During β- decay, a neutron within the nucleus transforms into a proton, accompanied by the emission of an electron and an antineutrino. This leaves the daughter nucleus with one more proton and one fewer neutron than the parent nucleus. The reaction equation for a β- decay is as follows:

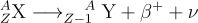

Here, X is the parent nucleus, Y is the daughter nucleus, Z is atomic number, A is atomic mass number, β is the beta particle and ν is the neutrino.

Conversely, in β+ decay, a proton transforms into a neutron, emitting a positron and a neutrino. This leaves the daughter nucleus with one fewer proton and an additional neutron compared to the parent nucleus. The reaction equation for a β+ decay is as follows:

While neutrinos are challenging to detect due to their weak interactions with matter, it is easy to detect the emitted electrons or positrons through their interactions with the surrounding medium. Furthermore, beta decay often leaves the daughter nucleus, Y, in an excited state. This excited nucleus subsequently de-excites by emitting gamma ray photons. These gamma rays carry characteristic energies corresponding to the specific energy level transitions within the daughter nucleus. By analyzing the energies of these gamma rays, it's possible to identify the parent isotope that underwent beta decay.

Beta Decay Feynman Diagram

Understanding the underlying physics behind beta decays requires a good understanding of fundamental particles and forces. Both β- and β+ decay reactions can be depicted using Feynman diagrams (seen below). These should be read from bottom to top, with progressing time on the y axis.

The protons and neutrons that make up atomic nuclei, are made up of sub-atomic, fundamental particles known as quarks. A proton consists of two "up" quarks and one "down" quark, and a neutron has one "up" quark and two "down" quarks.

During beta radiation, one quark changes type via the weak interaction force - one of the fundamental forces that determine particle interaction. This change in quark state from an "up" to a "down" or vice versa, causes the emission of a W boson particle.

The W boson, a carrier of the weak force, is a highly unstable particle due to its large mass. Therefore, the W boson quickly decays into an electron and an antineutrino or into a positron and a neutrino. These decay products are both fundamental particles (like the up and down quarks that make up protons and neutrons).

Beta Decay Spectra and Measurement

As neutrinos are weakly interacting, it is easiest to detect the electrons or positrons emitted from a beta decay. The energy spectrum of emitted beta particles is continuous as the available decay energy is shared among the beta particle, the neutrino, and the recoiling daughter nucleus. Since the energy distribution between these particles is not fixed, the beta particle's energy exhibits a continuous spectrum, ranging from zero up to a maximum value known as the "endpoint energy." The broad spectrum of beta decays limits its usefulness in direct isotope identification. However, this endpoint energy is characteristic for specific beta decay transitions.

Another measurable output of beta plus decays can be a pair of gamma rays produced through particle annihilation. The positron produced in a beta plus decay will quickly encounter an electron from a nearby atom, causing annihilation. This will create two photons with an energy of 511 keV each.

Additionally, if the beta decay creates a daughter nucleus, Y, that is in an excited state, the excited nucleus will relax into a lower energy state, emitting gamma ray photons. These gamma rays will have energies corresponding to energy levels within the daughter nucleus. Measuring the energies of emitted gamma rays can help identify the parent nucleus. An important example of beta minus decay with gamma ray emission is the decay of 137Cs, a relatively long-lived radioactive isotope commonly created in nuclear fission of 235U.

The study of beta decays has profound implications and applications in fundamental physics.

- Beta decay can be used to create a reliable source of neutrinos or positrons. For example, beta plus decay is the process used to create positrons for positron emission spectroscopy.

- Some isotopes, such as 136Xe, undergo rare double-beta decay, emitting two neutrinos and two electrons at the same time. Detecting the rarer neutrinoless variant would provide crucial information about the mass of the neutrino, one of the most elusive fundamental particles in the universe. Experiments like Lux-Zeplin (LZ) are currently searching for this elusive process.

- Precise measurements of the beta particle energy spectrum, particularly the endpoint energy, may also provide crucial information about the mass of the neutrino. The KATRIN experiment is dedicated to measuring the electron neutrino mass with high precision by carefully analyzing the beta decay spectrum of tritium.

Beta decay is a cornerstone of nuclear physics, shedding light on the fundamental forces and particles that govern our universe. By studying the intricate processes and energy spectra involved, we can unlock deeper insights into the building blocks of matter and the forces that shape the cosmos.

Further Resources

The groundbreaking work of Becquerel, the Curies, and Rutherford studying radioactivity revealed a diverse range of radiation types and their interactions with matter. This field has captivated scientific and societal interest for over a century, with billions of dollars invested globally in research.

Read more...In the field of particle physics, Compton scattering is a key principle for understanding the interaction between light and matter, alongside the photoelectric effect at lower energies, pair production at higher energies, and photodisintegration and photofission at very high energies.

Read more...Contributors

Written by

Product Developer

Diagrams by

Graphic Designer

Further Reading

- Radiation Detection and Measurement (Fourth Edition), G. F. Knoll, Wiley (2010)