Perovskite Quantum Dots

CAS Number 15243-48-8

Low Dimensional Materials, Materials, Nanodots and Quantum Dots, Perovskite Materials,High purity, high PLQY Perovskite Quantum Dots

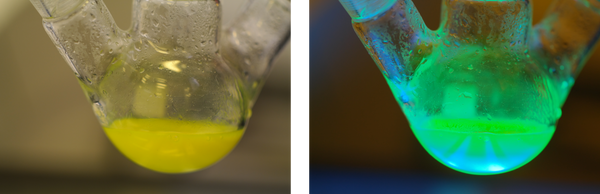

Readily soluble caesium lead bromide (CsPbBr3) perovskite quantum dots powder

Technical Data | MSDS | Literature and Reviews

Perovskite quantum dots are currently unavailable. Please see our related products:

Perovskite quantum dots (CAS number 15243-48-8) are semiconducting nanocrystals. Compared to metal chalcogenide quantum dots, perovskite quantum dots are more tolerant to defects and have excellent photoluminescence quantum yields and high color purity. These properties are highly desirable for electronic and optoelectronic applications and hence perovskite quantum dots have huge potential for real world applications including LED displays and quantum dot solar cells.

Highly tolerant

Highly tolerant to defects, retain high PLQY

High purity

99% Quantum Dot Purity

Worldwide shipping

Quick and reliable shipping

Semiconductor

Semiconducting nanocrystals

Caesium lead bromide (CsPbBr3) perovskite quantum dots powder is readily soluble in hexane, octane, and toluene.

Technical Data

CsPbBr3 Perovskite Quantum Dots Powder

| CAS Number | 15243-48-8 |

|---|---|

| Chemical Formula | CsPbBr3 |

| Molecular Weight | 579.82 g/mol |

| Full Name | Caesium lead tribromide quantum dots powder |

| Synonyms | Caesium lead bromide quantum dots |

| Classification / Family | Perovskite quantum dots, Perovskite nanocrystal solutions, Cadmium-free quantum dots, Quantum dot solutions, Green emitter, Quantum dot LEDs (QDLEDs), Perovskite LEDs (PeLEDs), Perovskite solar cells (PvSCs) |

| Purity | 99% |

| Appearance | Yellow powder |

| Emission Peak | 515 – 520 nm |

| Photoluminescence Quantum Yield | 83% |

| Solubilising Solvent | Hexane, octane, toluene |

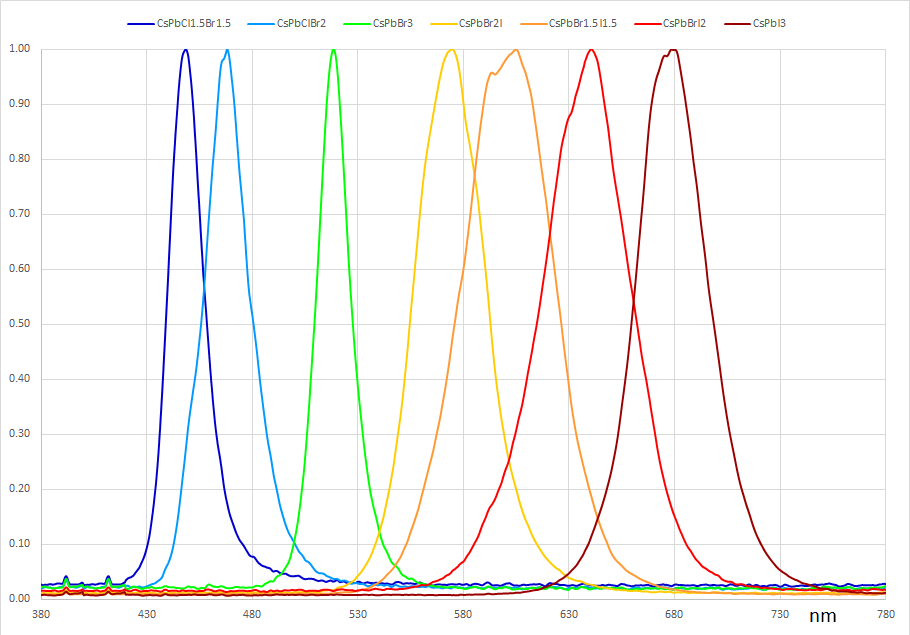

Perovskite Quantum Dot Spectral Data

CsPbBr3 Perovskite Quantum Dots Absorption Spectra

CsPbBr3 Perovskite Quantum Dots Absorption Spectra

CsPbBr3 Perovskite Quantum Dots Photoluminescence Spectra

CsPbBr3 Perovskite Quantum Dots Photoluminescence Spectra

MSDS Documents

CsPbBr3 Perovskite Quantum Dots Powder MSDS Sheet

What is a Perovskite Quantum Dot?

A new class of quantum dot is emerging based on perovskites. These have already been shown to have properties rivalling or exceeding those of metal chalcogenide QDs.

Due to their outstanding photovoltaic performance, perovskites are receiving significant attention from the research community. Recently, has been shown that reducing the dimensions of a perovskite crystal down to a few nanometres results in the creation of quantum dots with very high photoluminescence quantum yields and excellent color purity (i.e., narrow emission linewidths of ~10 nm for blue emitters and 40 nm for red emitters [1]).

These quantum dots are highly tolerant to defects, as they require no passivation of the surface to retain their high PLQY. Although defect and trap sites are present, their energies are positioned outside the bandgap and are either located within the conduction or valence bands [2]. Such perovskite nanocrystals are simple to synthesise in a colloidal suspension and are easily integrated into optoelectronic devices using readily available processing techniques, making them a strong contender for future technologies.

Applications of Perovskite Quantum Dots

Perovskite quantum dots have huge potential for a range of applications in electronics, optoelectronics, and nanotechnology. Currently, the field is not well researched, but initial results are extremely promising. Details on a selection of the applications that have been investigated are given below.

Quantum Dot Solar Cells

Currently, reports of perovskite quantum dot solar cells are still limited, especially when compared to bulk and 2-dimensional perovskites. This is likely due to the limited time that such materials have been available. However, recent results suggest that perovskite quantum dots could play a role in future photovoltaic devices.

The first use of perovskite quantum dots in solar cells was in 2011 by Im et al., where MaPbI3 nanocrystals acted as a light-sensitiser in a structure resembling a dye-sensitised solar cell [16], with a power conversion efficiency of 6.5% reported. This result predated the synthesis of colloidal perovskite quantum dots, and the nanocrystals were instead formed through surface interactions when a mixture of methylammonium iodide and lead iodide was spin cast onto a TiO2 surface.

At room temperature, bulk CsPbI3 forms an orthorhombic crystal lattice with a large bandgap of ~2.8 eV. The cubic phase is far more suitable for photovoltaic applications as a result of a narrower bandgap (1.73 eV). However, this phase only forms in bulk CsPbI3 at temperatures above 300 °C. Due to the elevated temperature and the effect of reduced surface area, all CsPbX3 nanocrystals crystallise into the cubic phase during synthesis. In contrast CsPbCl3 and CsPbBr3 quantum dots are phase-stable in the cubic polymorph over long periods, however CsPbI3 will convert back to an orthorhombic configuration over a few days in ambient conditions.

Swarnkar et al. showed that treating spin cast CsPbI3 quantum dot films with methyl acetate stabilises the cubic structure [17]. This was achieved by changing the surface energy via the removal of unreacted precursors — without causing the aggregation of the dots. The resulting film was stable for months under ambient conditions and had excellent optoelectronic properties. Indeed, when fabricated into solar cells, such films achieved a PCE of over 10% and had a large open-circuit voltage of 1.23 V. Furthermore, LEDs incorporating stabilised CsPbI3 nanocrystals as the active layer displayed a low turn-on voltage of < 2 V.

It was later demonstrated that coating the nanocrystals in A+X- (where A is formamidinium, methylammonium or Cs, and X is I or Br) further improves charge-carrier mobility of the nanocrystal films. This allowed solar cells having a PCE of 13.4% to be fabricated — the highest efficiency photovoltaics based on quantum dots of any kind [18]. This result is promising for the development of perovskite tandem solar cells; here a bulk perovskite film performs the role of the low bandgap absorber, with the perovskite quantum dot layer acting as a complementary wide bandgap absorber[19].

Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs)

Metal chalcogenide quantum dots already play a role in consumer display products — so the increased PLQY, ease of synthesis, excellent color purity, and wide color tunability of perovskite quantum dots suggest that they should be well-suited to such applications. However, charge injection and transport in nanocrystal films must be optimized in order to achieve high-efficiency devices.

First devices by Song et al. used an ITO/PEDOT:PSS/PVK/CsPbX3/TPBi/LiF/Al structure to demonstrate blue, green, and orange LEDs [11]. While the emission linewidths were narrow, the brightness of the LEDs was modest (<1000 cd m-2), and the external quantum efficiencies (EQE) were limited to ~0.1%.

Li et al. showed the importance of nanocrystal surface chemistry; here the EQE of CsPbBr3 nanocrystal LEDs was increased by 50x (0.12% to 6.27%) through the optimization of device charge-transport layers and surface ligand density control (achieved through the use of a washing procedure using hexane and ethyl acetate [3]). While ligands are needed to passivate the quantum dot surface and prevent aggregation (leading to high PLQY and greater stability), an excessive density of surface ligands can inhibit electrical injection and transport. By tuning the ligand density, a brightness of >15,000 cd m-2 was obtained that was accompanied by high color purity (20 nm emission linewidth using ~8 nm nanocrystals).

One proposal that bypasses the electrical properties of nanocrystal films is to use them as down-converters for inorganic blue or UV LEDs. Pathak et al. dissolved hybrid organic-inorganic perovskite quantum dots of various mixed halide compositions (emitting green or red luminescence) into a polystyrene polymer solution which was then spin cast into a thin film [12]. The polystyrene polymer acted as an insulating matrix that prevented anion exchange, thereby preserving the individual emission peaks of the constituent nanocrystals and allowing the generation of white light when illuminated with a commercial blue LED.

Lasers

Amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) has been observed in drop cast films of CsPbBr3, and mixed CsPb(Br/I)3 and CsPb(Cl/Br)3 nanocrystals. Pump thresholds can be as low as 5 µJ cm-2 [13]; a value that compares very favourably with other colloidal QD systems (e.g., an order of magnitude lower than spectrally similar CdSe QDs). The ASE emission intensity is extremely stable in air, dropping by only 10% after several hours of irradiation and ~107 shots in ambient conditions. This performance also compares extremely well to chalcogenide QDs [14]. The stimulated emission has been identified as resulting from the recombination of biexcitons (which are more stable at room temperature than excitons), with red-shifted emission leading to reduced self-absorption (and hence low lasing thresholds). The ASE wavelength can also be tuned throughout the entire visible spectrum via mixing the halide composition.

Lasing was observed in a whispering gallery mode configuration. It was later shown that stimulated emission could be observed in CsPbBr3 nanocrystal films following two-photon absorption [15]. Here, it was found that the two-photon absorption cross-section was 2 orders of magnitude larger than that of similar metal chalcogenide quantum dots, leading to a stimulated emission threshold of green-emitting CsPbBr3 nanocrystals of 2.5 mJ cm-2. This is far lower than core-shell metal chalcogenide quantum dots. This non-linear stimulated emission could also be tuned across the visible wavelengths by varying the mixed halide composition. Green stimulated emission from CsPbBr3 quantum dots (following three-photon absorption) was also observed — a first for any type of quantum dot. For this reason, perovskite quantum dots present an exciting prospect for the development of next-generation lasers.

Singler Photo Sources

Single photon sources are required for new light-based quantum information systems. Here, current efforts mainly focus on the use of epitaxially-grown quantum dots, diamond color centers and colloidal nanocrystals. Of these, colloidal NCs are the most promising for room-temperature visible operation [20].

Dilute CsPbX3 (X=Br, I or Br/I) NC solutions have been spin cast to create spatially-separated individual QDs [20,21]. Imaging the photoluminescence from individual NCs showed the blinking behaviour that is characteristic of single emitters. Photon coincidence counting revealed low g(2) values of ~6%, demonstrating the realisation of an efficient, anti-bunched single photon source at room temperature — all of which are desirable characteristics for emergent quantum technologies.

In comparison with metal chalcogenide QDs, metal halide perovskite QDs display shorter fluorescence lifetimes and higher absorption coefficients and are therefore faster and more efficient sources of single photons.

Photodetectors

The high absorption coefficient of perovskite QDs over a wide spectral range may make them suitable candidates for use in light-detection devices. Pan et al. have reported the fabrication of a phototransistor based on FAPbBr3 quantum dots and graphene [22]. The QDs which act as the light absorber, are deposited onto a monolayer of graphene that transports photoexcited charges to the source/drain. Such phototransistors have a broad response spanning the visible spectrum, although they have reduced response to photons having energies below the semiconductor bandgap (540 nm). Here, a photoresponsivity of 1.15×105 AW-1 was observed at 520 nm; a value that is amongst the highest of any graphene-based photodetectors.

Perovskite Quantum Dot Structure

Halide perovskite nanocrystals have a cubic crystal structure with the chemical formula A+Pb2+X-3. They can be classed as an organic-inorganic hybrid, where A is an organic cation such as methylammonium (MA) or formamidinium (FA), or fully inorganic (A=Cs), and where X is a halogen (Cl, Br, or I). Due to the lack of volatile organics, fully-inorganic nanocrystals tend to have better stability and higher PLQY (>90%) than hybrid organic-inorganic materials [3]. Mixed halide perovskites can also be produced where X is a mixture of Cl/Br or Br/I.

For visible optoelectronic applications, the nanocrystals are generally synthesised to have a size of 4 – 15 nm (dependent on the halogen atom and the required optical properties). The emission wavelength can be tuned through the entire visible spectrum (400 – 700 nm [4]) by changing either the nanocrystal size or halide ratio (for mixed halide systems).

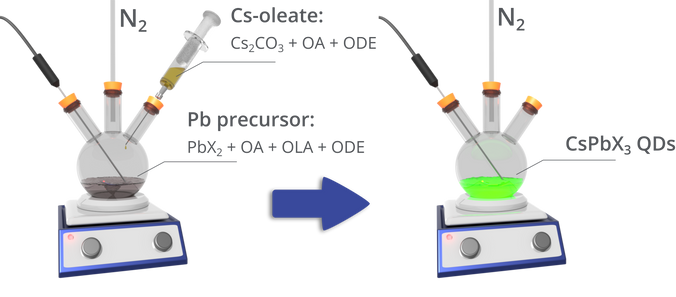

Perovskite Quantum Dot Synthesis

The first hybrid organic-inorganic perovskite quantum dot colloidal synthesis of MAPbBr3 was reported by Schmidt et al. using a hot injection method (similar to that used to synthesise metal chalcogenide QDs [4]). A mixture of methylamine bromide and lead bromide was injected into an octadecene solution containing oleic acid and a long chain alkyl ammonium bromide. The PLQY of the resulting QDs was ~20% and was stable for several months due to the stabilising and capping effects of the ammonium bromide and oleic acid. By optimization of the reactant molar ratios, the PLQY was increased to over 80% [5], and later to ~100% by changing the capping ligand [6].

Hot injection was again used for the colloidal synthesis of inorganic metal-halide perovskite quantum dots, first reported by Protesescu et al [1]. That recipe developed was as follows:

- The caesium precursor Cs-oleate is first prepared by mixing caesium carbonate (Cs2CO3) and oleic acid (OA) in octadecene (ODE), and heating under nitrogen until the Cs2CO3 has reacted with the OA. This solution must be kept above 100 °C to prevent precipitation of the Cs-oleate.

- A lead halide precursor is prepared by mixing a lead halide (PbCl2, PbI2, PbBr2 or a mixture of these) in ODE at 120 °C under nitrogen, along with OA and oleylamine (OLA) that act as stabilising agents. Once the lead halide has dissolved, the temperature is increased to between 140 – 200 °C (depending on the required nanocrystal size).

- The caesium precursor is then injected. After 5 seconds, the mixture is rapidly cooled in an ice bath, with the quantum dots being isolated through centrifuging.

The resulting nanocrystals have surface ligands comprised of OA and OLA [3]. Such nanocrystals were found to have PLQYs up to ~90%, with the smallest crystals (4 nm diameter) having an emission linewidth (full width half maximum) of 12 nm at an emission wavelength of 410 nm, with the largest quantum dots (15 nm diameter) having a linewidth of 42 nm at 700 nm.

Mixed-Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots

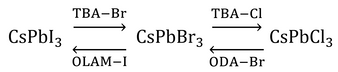

An advantage that perovskite quantum dots have over their metal chalcogenide counterparts is the simplicity by which their emission properties can be modified. In addition to tuning the emission wavelength during synthesis through reaction temperature (and ultimately, nanocrystal size), it can also be changed post-synthesis through an anion-exchange reaction [7,8]. By mixing a donor halide source such as octadecylammonium (ODA-Y), chloro-oleyalmine-oleylammonium chloride (OLAM-Y) or tetrabutylammonium (TBA-Y) halide (where Y is Cl, Br or I) with a solution of CsPbX3 nanocrystals, the chemical composition of the nanocrystals can be tuned continuously over the range CsPb(X1-Z:YZ), where 0≤Z≤1.

Anion exchange is followed by lattice reconfiguration, giving a mixed halide structure. This results in a single emission peak at an energy somewhere in between those of the constituent nanocrystals, thereby retaining the narrow linewidth needed for color purity. However, it has been found that direct conversion between CsPbI3 and CsPbCl3 is not possible because of the large mismatch in the size of the halide ions.

It has also been demonstrated that this anion exchange process can be easily accomplished by simply mixing different stock solutions of the nanocrystal constituents at different volume ratios (e.g., CsPbBr3 and CsPbI3 to obtain CsPb(Br1-Z:IZ)3 [7,9]). Both methods allow the nanocrystal emission to be tuned over the entire visible range while retaining a high PLQY and color purity. The anion exchange process can however be suppressed by adding polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) to the solution. This creates a protective cage around the nanocrystals and allows mixing of different halide compositions while retaining the photoluminescent properties of the constituent nanocrystals. It also has the added effect of protecting the nanocrystals from water [10].

Literatures

- Nanocrystals of Cesium Lead Halide Perovskites (CsPbX3, X = Cl, Br, and I): Novel Optoelectronic Materials Showing Bright Emission with Wide Color Gamut, L. Protesescu et al., Nano Lett., 15 (6), 3692–3696 (2015)

- Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals in the Research Spotlight: Stability and Defect Tolerance, Huang et al., ACS Energy Lett., 2 (9), 2071–2083 (2017)